Luck is a very thin wire between survival and disaster, and not many people can keep their balance on it. - Hunter S. Thompson

Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act. There is no other route to success. - Pablo Picasso

This blog is not a typical blog post but is in fact a paper that I wrote that some asked to see. It is dry and academic - if you don’t like such things, please come back later.

We live in a world that stands on the pinnacle of science and knowledge and yet despite our deep understanding of things such as human behavior, many things in the world, especially in the areas of business and government, continue to struggle with often-unpredictable results. Governments rise and fall despite their best intentions and businesses, despite their access to knowledge in the areas of business forecasting, customer behavior analysis and such, continue to surprise or disappoint people. Examples include the unexpected success of a small college-centric social media start-up that became Facebook and the quick demise of Blackberry, the company that essentially defined the smart phone market.

Why does humanity, with its access to knowledge, idea frameworks, best practices and technology, still appear to be executing randomly, with poor execution still as likely as strong execution? I submit that John Kingdon’s organized anarchy theory (also known as garbage can theory) explains this supposed randomness perfectly. I also submit that in understanding this apparent randomness that perhaps some of the randomness can be strategically removed to produce a better result.

In his book, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies[i], Kingdon suggests that one can recognize an organized anarchy as having the following characteristics:

- Ill-defined goals, problematic preferences and inconsistent identities

- Unclear technology

- Fluid participation

- Independent streams of solutions, problems, participants, and choice arenas

The difficulty with such characteristics is not so much the existence of them but rather who defines them.

For example, if a business or government leader has specific goals, someone who has conflicting goals or intentions might characterize the others as having ill defined or problematic goals. The technology within the problem domain may be clear to someone with expertise in that domain but may be unclear to others who have experience with different (not necessarily superior or inferior) domains.

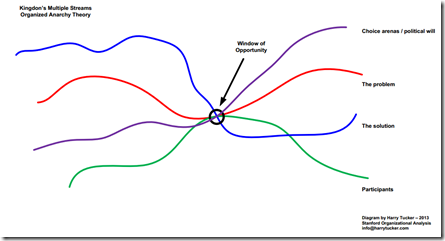

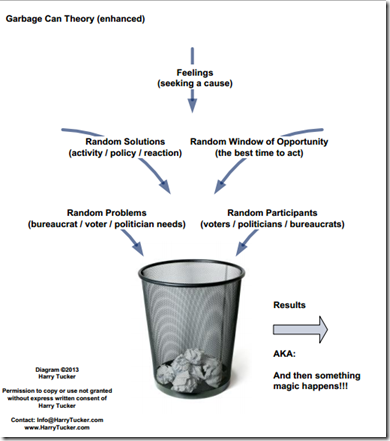

When one thinks about the independent streams that Kingdon describes, it almost appears totally random as demonstrated in the attached diagram (click on the image for a higher resolution image).

The diagram demonstrates the “Holy Grail” that comes into existence when all of the streams come together – the opportunity to create public policy or make decisions by governments or businesses respectively. Unfortunately, the diagram also suggests a significant amount of randomness present that makes such a Holy Grail elusive.

Some might suggest that one can simply observe progress along the different streams and prepare to execute as they coalesce, thus removing randomness from the process. Unfortunately, the streams themselves are quite fluid, shifting constantly and so predicting a coalescing of the streams is not easily performed given that the intersection point itself is not static along each of the streams.

In addition, I would like to add an additional stream to the mix, the stream being one of feelings, agendas or motives, both on the part of those whose execution will produce a result (represented as intention) and on the part of those impacted by execution (represented as expectation).

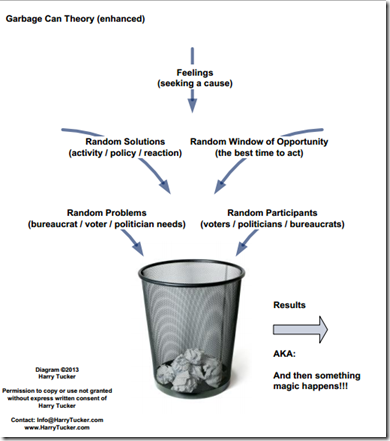

Given that all of these streams coalesce into somewhat of a random collection of events, intentions, problems and solutions, I believe the multiple streams are more accurately represented as a true garbage can as shown in the attached diagram (click on the image for a higher resolution image).

What are the possible ramifications of such random execution?

In a study conducted by Kathleen Tierney of the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware[ii], Ms. Tierney posited that:

“Of the four key disaster phases or management tasks (mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery), mitigation has been studied the least (Drabek 1986a) and is probably the least well understood.”

She went on to say that hazards to government and business that could be avoided but which are not are as the result of:

“Being at the ebb and flow of public and elite interest, and many alternate strategies, including various mitigation approaches, are available to deal with them”.[iii]

This suggests that disaster avoidance within government and business is almost totally random at best unless an equally random opportunity to address the problem arises.

Alesch and Petak, in their study “The Politics and Economics of Earthquake Hazard Mitigation” [iv], noted the following:

“Windows of opportunity are essential for hazard mitigation policy to be enacted. Windows can be pried open with enormous continuing effort but they open automatically in the event of a low probability / high consequence event that demands community attention.”

In other words, the best time to come up with policy decisions within an organized anarchy seems to arrive after a similar disaster has already occurred. This is cold comfort to those who have lived through the previous disaster. It is also complicated by the fact that even when the perfect window has arrived, it must be executed within constraints that exist at the moment in the areas of time, energy and money before the political will fades or the opportunity is diverted to some other perfect coalescing of the streams as described by Kingdon.

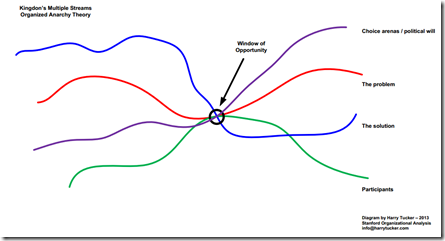

If we zoom in on governments for a moment, this problem is exacerbated with the knowledge that the problem or opportunity participants form three distinctive camps with three different sets of problems, solutions and expectations:

The electorate – wanting good schools, hospitals, roads and other infrastructure and wanting it immediately. Electorate needs are often immediate and of short-term duration, with voters tending not to look at the long-term picture.

The politician – wanting to serve their constituents as well as possible (hopefully true but not always) with their primary focus still being on getting re-elected in 4 years (or whatever the term of office is). Their focus on getting re-elected makes their horizon medium term in duration, acknowledging their electorate’s needs while recognizing that a single term in office may not be sufficient to answer to those needs (or their own needs in some cases).

The bureaucrat – wanting to execute their long-term strategic intentions without interference (and sometimes knowledge) of the electorate or the politician. This reflects a long-term need, often seeing strategy in 20-year windows or longer.

The difficulty of such a partnership is shown in the attached diagram (click on the image for a higher resolution image).

So the question becomes this:

If the results of our governments and businesses are in fact truly the random coalescing of all of these streams, representing the dark complexity of organized anarchy, what can we do to avoid an inadvertent total disaster that must be statistically inevitable if our execution is reduced to luck?

I posit that we need a more strategic approach to nullify the randomness that is so well-described in Kingdon’s organized anarchy theory. This strategic approach would have an almost “return-from-the-future” type effect that provides the strategy practitioner with an opportunity to understand the streams as they played out in the future and to work backwards from the end of the streams to identify where the coalescing actually took place.

While a “return-from-the-future” effect exists primarily in the realms of H.G. Wells or Hollywood, I believe there is a way to be accurate in predicting the outcome from random participants, problems, events and the like.

It is through the use of a process called backcasting.

Backcasting is defined as:

“Defining a desirable future and then works backwards to identify policies and programs that will connect the future to the present. The fundamental question of backcasting asks: "if we want to attain a certain goal, what actions must be taken to get there?" Forecasting is the process of predicting the future based on current trend analysis. Backcasting approaches the challenge of discussing the future from the opposite direction.”[v]

The attached diagram illustrates a high-level mind map of backcasting (click on the image for a higher resolution image).

In the process of executing a backcasting process, one attempts to define a future state as having already occurred and then stepping backward, asking one’s self what has to have happened before the current step in order for the current step to occur. With the previous step defined, one then asks what has to have happened prior to that step in order for the previous step to have occurred and so on until one reaches one’s current state with its collection of participants, problems, solutions and other entities as defined by Kingdon.

The process of backcasting allows the strategic observer to remove the mystery from a future event by forcing the understanding of all the resources in play; knowledge, money, interdependencies and the most seemingly random resource of all, people. It forces the strategic observer to understand the motivators, intentions, intelligence, knowledge and other elements of the participants and in doing so, takes much of the randomness out of the equation.

How effective is such a process?

In March of 2008, the author of this paper, as a long time Wall St. strategy advisor, wrote a blog warning of the coming financial collapse in September of 2008. The blog, entitled “Financial Crisis”[vi], publicly identified when the collapse would occur and named the two financial institutions, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch, that would disappear as a result of the event. Financial institutions who foresaw the crash and who read blogs such as this one protected their assets while many people and organizations lost everything.

Meanwhile, in the months leading up to the crash, groups such as the US Federal Government and other organizations were predicting that the nation was on the cusp of greatness.

For example, on February 28, 2008, MSN’s real estate column wrote that “now” was the perfect time to buy into real estate[vii] , encouraging young people and renters with this line:

“Sliding prices and desperate sellers may seem to make this the perfect time for young renters to buy their first home.”

The Insurance Journal released a study on July 23, 2008 entitled “US Entrepreneurs More Optimistic on Taking Risks”[viii], where they noted the following outlook on entrepreneurs and business:

“Overall, their outlook is very optimistic,” added Donnelly. “People are choosing a new path of self-direction and welcoming what lies ahead.”

Less than two months later, most of these businessmen were wiped out.

And finally, the New York Times on January 23, 2008, quoted[ix] then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice when she described the US and global economy this way:

“Its long-term economic fundamentals are healthy,” said Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice of the United States in a speech Wednesday at the World Economic Forum. She declared that President Bush had provided an “outline of a meaningful fiscal stimulus policy.”

The author of the New York Time article closed the article with this prophetic quote:

“As I write this, her speech is continuing, uninterrupted by applause.”

Months later, we experienced the worst economic collapse in world history with its remnants still affecting us today.

Having sat in many Wall St. and government meetings in the months and years leading up to the events of September 2008, Kingdon’s organized anarchy theory was prevalent everywhere. We were plagued by agenda-less meetings that invited people for no other reason than to make it look like they were contributing to “something”, even though without an agenda, why many people were present was a mystery to all of us and without a problem being defined (the pending crash), their contribution was unknown anyway. We executed meetings daily in blind denial of the events that were unfolding.

In the end, some of us recognized that garbage can theory in its purest definition was alive and well, but unfortunately, critical deadlines were approaching that the participants in the garbage can seemed unaware of or uncaring about as they focused on personal agendas that were meaningless and trite (and would mean nothing once the economic collapse arrived).

It was because many of us recognized that garbage can theory was in fact leading us blindly to the abyss that we switched to backcasting theory to predict the time, scope and scale of the pending event, factoring in the same elements as Kingdon describes but doing so in such as way as to remove as much of the randomness as possible.

In other words, garbage can theory will eventually produce a result but sometimes one has to take the randomness out of it using other theories when critical deadlines appear on the horizon.

By taking the key elements of garbage can theory, namely,

- Ill-defined goals

- Unclear technology

- Fluid participation

- Independent streams of solutions, problems, participants, and choice arenas

and my optional additional element of feelings, agendas and motives and evaluating them strategically using a process like backcasting instead of leaving them to the randomness of the garbage can, one has a better opportunity to make policy or business decisions that are more appropriate, more timely and more effective to the people they serve.

More organizations are recognizing the importance of finding time-sensitive solutions and are embracing the less random, more accountable results from backcasting, including but not limited to[x]:

- fms - The Division for Environmental Strategies Research, Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden

- Global Scenario Group

- Institute for Sustainable Futures

- The London Perret Roche Group LLC

- Pacific Institute

- POLIS Project on Ecological Governance

- POLIS Water Sustainability Project

- Tellus Institute - environmental research group that uses backcasting to develop strategies for sustainability

- The Natural Step

- Sustainability department at the Blekinge University of Technology

- Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford, UK

Unfortunately, finding solutions to the challenges from garbage can theory increase public accountability and responsibility, something that often contradicts with the public intentions of businessmen and politicians. I wonder if this is why we still prefer the randomness of garbage can theory when more effective practices exist.

Only the writers of our history books will know for sure.

References (some links may be stale)

[i] Kingdon, J. W., Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, second edition, Pearson, 1995, Print

[ii] Tierney, Kathleen J., Improving Theory and Research on Hazard Mitigation: Political Economy and Organizational Perspectives (pp 367), International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, November 1989, Vol 7, No. 3, Print

[iii] Tierney , Kathleen J., Improving Theory and Research on Hazard Mitigation: Political Economy and Organizational Perspectives (pp 385), International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, November 1989, Vol 7, No. 3, Print

[iv] Alesch, Daniel J. and Petak, William J., The Politics and Economics of Earthquake Hazard Mitigation: Unreinforced Masonry Buildings in Southern California, University of Colorado – Institute for Behavioral Science – Program on Environment and Behavior Monograph #43, Print, 1986

[v] Widipedia, Retrieved from URL http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backcasting on November 8, 2013

[vi] Tucker, Harry, Financial Crisis, Harry Tucker – Observations and Musings, Retrieved from URL http://harrytucker.blogspot.ca/2008/03/financial-crisis.html on November 8, 2013

[vii] Editor, February 28, 2008, MSN Real Estate, Retrieved from URL http://realestate.msn.com/article.aspx?cp-documentid=13107821 on November 10, 2013

[viii] Editor, July 23, 2008, The Insurance Journal, Retrieved from URL http://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2008/07/23/92136.htm on November 10, 2013

[ix] Editor, January 23, 2008, The New York Times, Retrieved from URL http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2008/01/23/entering-a-no-gloom-zone/?_r=0 on November 9, 2013

[x] Wikipedia, Retrieved from URL http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backcasting on November 8, 2013